World War II Japanese Flag Translation

On a cold evening in February of 2012, I walked into my martial arts dojo to see my instructor speaking with another gentleman. I was going to pass by and get changed when I heard him call me over.

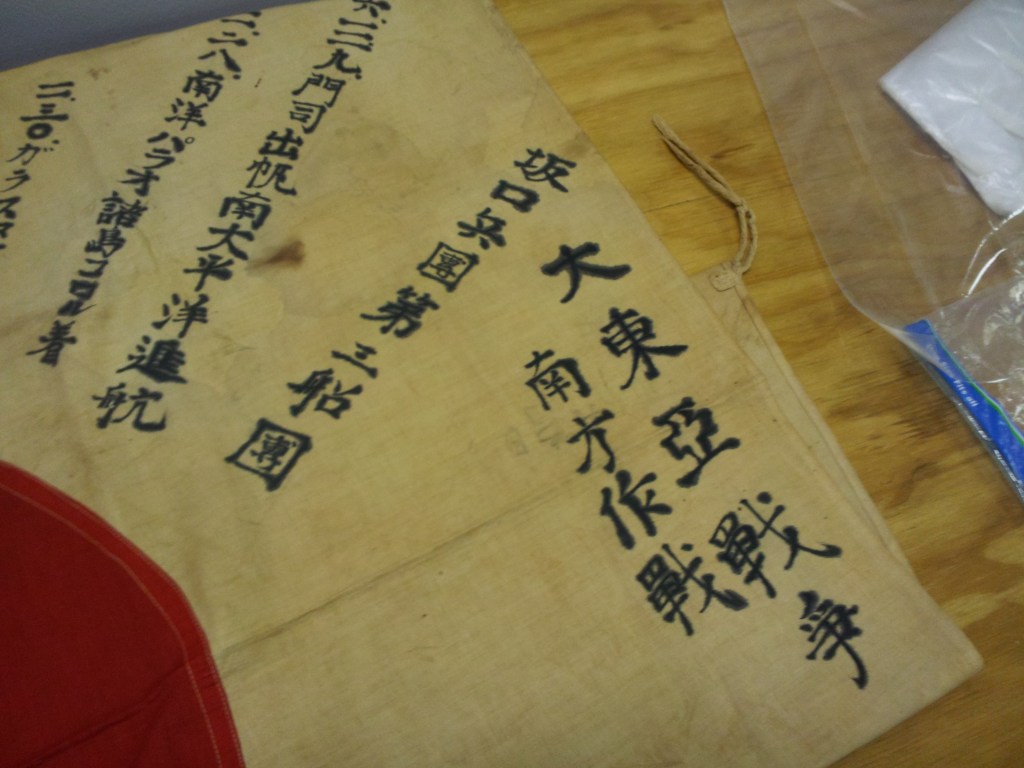

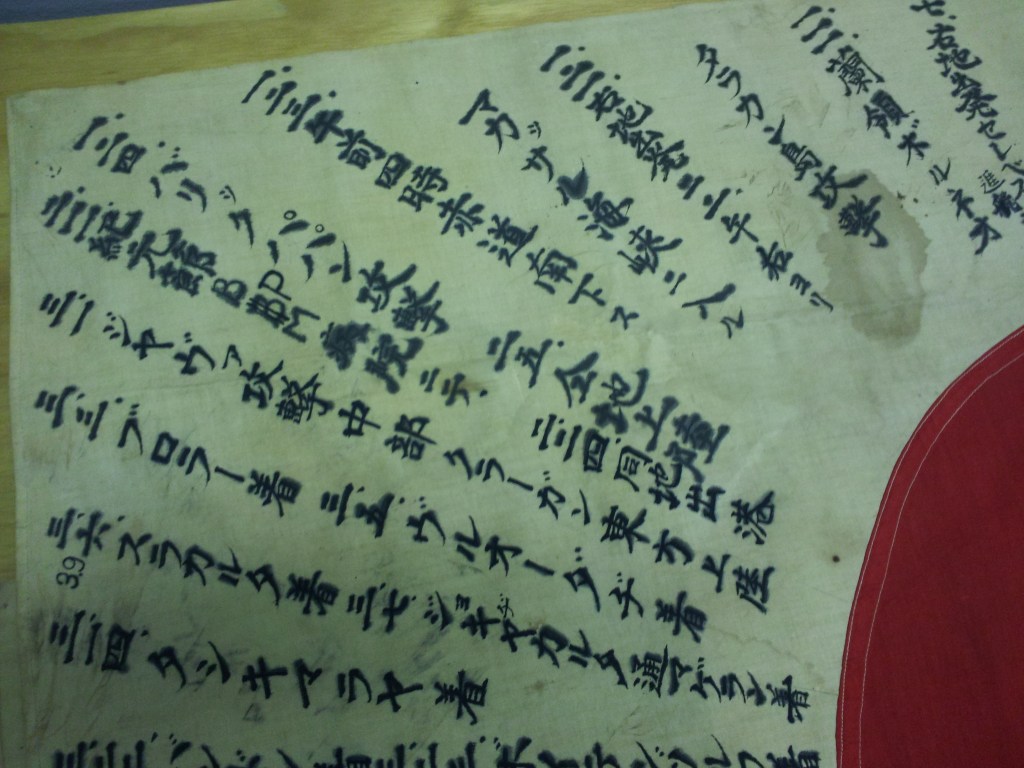

When I approached, there was an old Japanese flag stretched out across a wooden chest. My instructor, Sensei Noel, explained that the flag had been found in an ammo can down in the basement of a U.S. Marine’s home. It had been rolled up inside and tucked away, long forgotten for decades. Sensei Noel asked me if I could translate the flag for the gentleman.

At the time, I was still a senior in high school, but had been taking Japanese language classes after hours. I only had one semester under my belt with very elementary skills. Still, as I looked over the faded cloth, I realized this was an opportunity too great to pass up.

As a matter of assurance, Sensei Noel told me that they were going to have another Japanese man help with translation and then he and I could compare our translated texts.

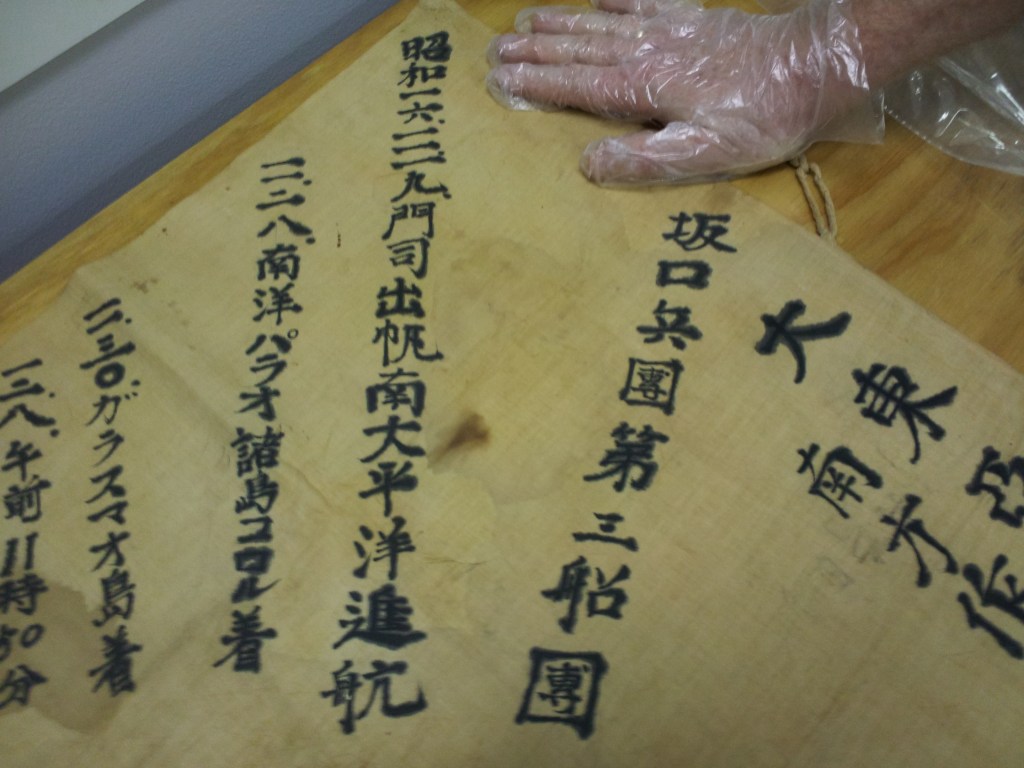

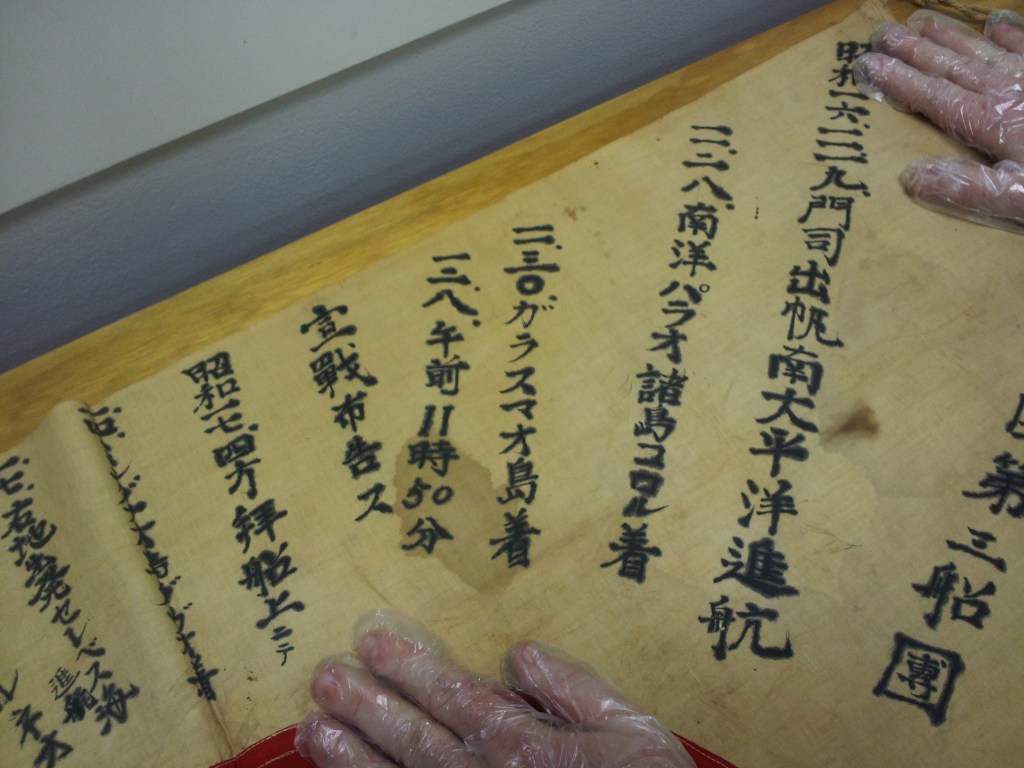

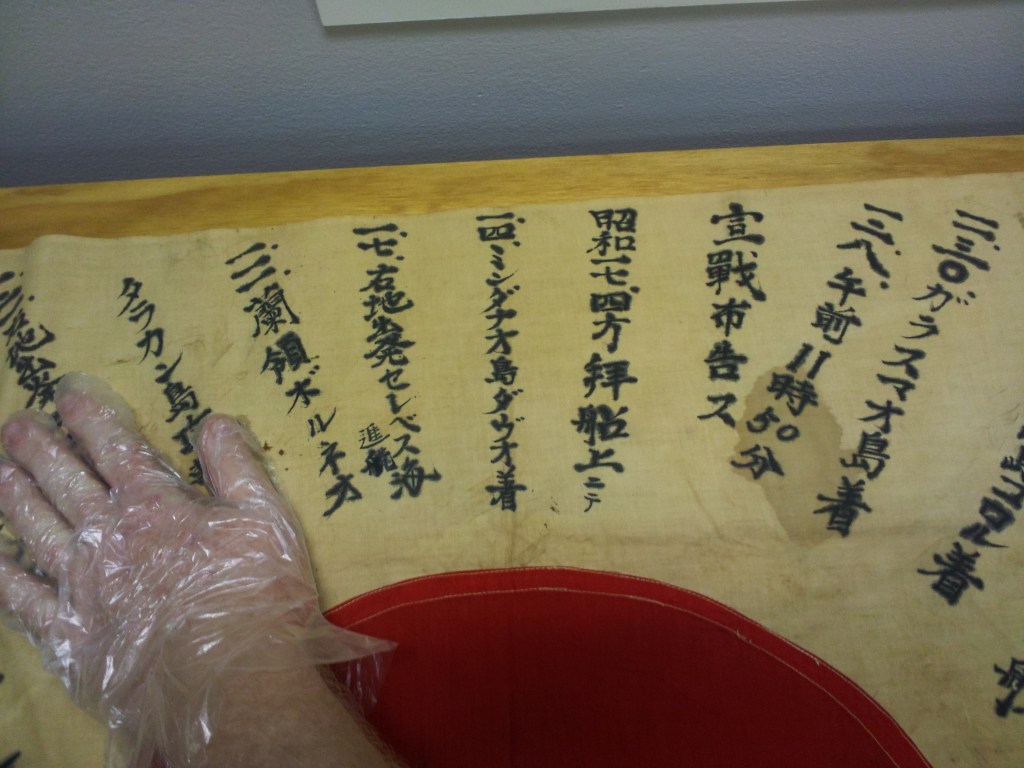

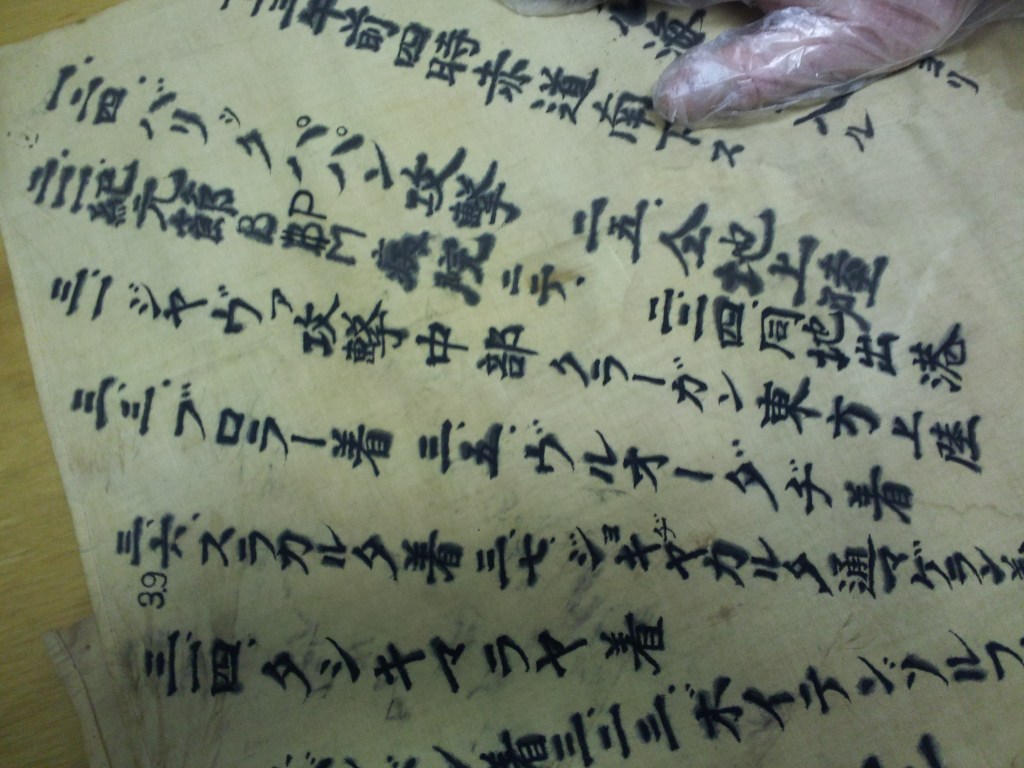

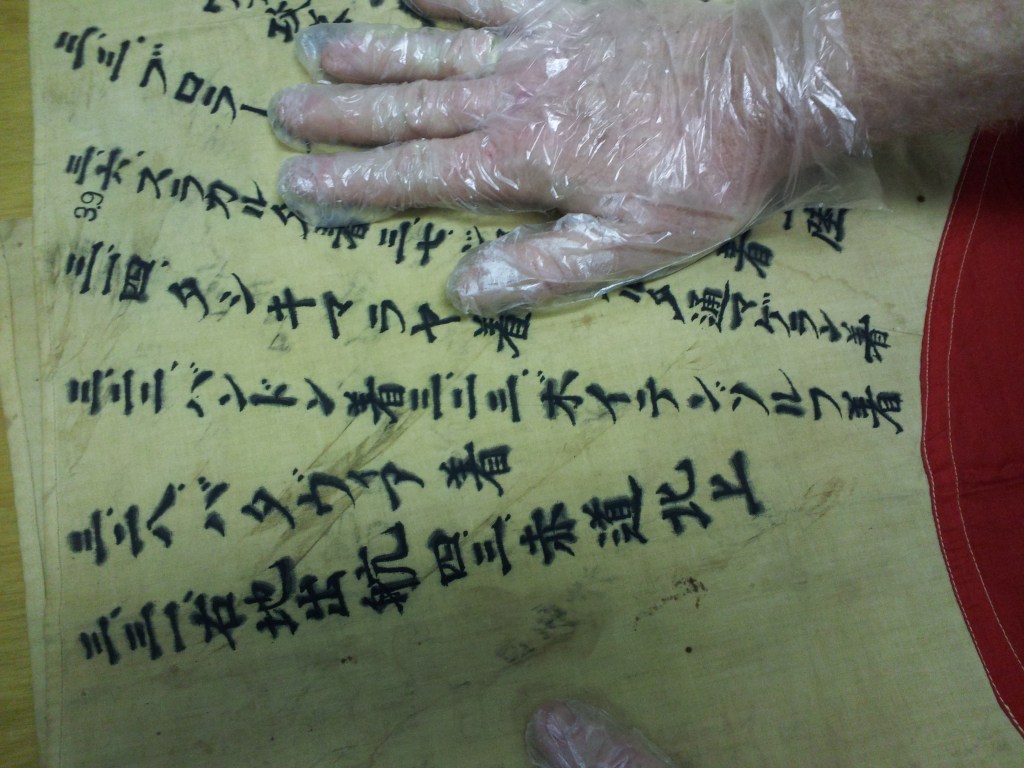

Since the flag was so old, there was no way I was going to be able to take it home with me. So, I took a series of pictures as the gentleman spread the flag out with gloved hands, ensuring I was able to take some quality shots.

To this day, I wish I had a full picture of the flag. At the time though, my pictures were a little more utilitarian in nature. Thankfully, they were good quality, but represent the flag in sections.

A Quick Note on Accuracy

As I stated before, I translated this flag with the rudimentary skills that I had. I do not claim that the translations which I have uploaded here are 100% accurate and I have yet to go back through and take a thorough second look. However, I wanted to post what I translated at the time to provide a snapshot of my capabilities when I was assigned the project. So, if you know Japanese and find inaccuracies in my translation, I’ll be the first to say that I am absolutely sure there are! This is part of the reason we had a second person working on the translation. What I provide here are my notes independent of the other translator (I will need to ask my Sensei for his name to give him the proper credit he deserves as well).

What I’m after here is capturing myself and this project as a moment in time. The documents provided are what I created back in 2012 and that is what I would like to display here.

Well, enough of that. On to the good stuff!

Translating the Text

I began by translating at my kitchen counter, and heavily relied on my dictionary, “imiwa?” (which literally means, “What’s the meaning?”). There were many unfamiliar kanji (the written characters), so it was a very slow process as I muddled through each column.

However, the more I translated, the more I realized that this was a Imperial Japanese soldier’s journal – specifically of his travels in the Pacific after leaving Japan. It delineated his arrivals and departures at various places in the South Pacific, including Java and the Philippines. This really started to give the flag an even greater importance.

When putting this together for web viewing, I was having trouble deciding on organization. I felt the best way would be to post sections of the flag with their translations underneath them. I’ll do the best I can to guide you as to which column is which…

Note that any text within brackets like these [ ] is my own commentary in which I share theories and results from research. Also, some columns are joined together, such as 14 and 15, for the sake of comprehending the sentence as a whole because it was spread out among two columns.

1.大東亜戦争(だいとうあせんそう)

The Pacific War (Greater East Asian War)

2.南方作戦(なんぽうさくせん)

Southern Strategy

3.坂口(さかぐち)夾圑(きょうほ)第三(だいさん)航圑(こうほ)

Sakaguchi, Kyouho III [I have surmised that this is the man’s name, though I cannot be certain. I was unable to understand how the last two characters fit together. In addition, the character 夾 was one I thought might be a variant of the third character, as I was unable to locate it. The character 圑 (the fourth and last characters in this column) is a variant of 圃, which is an NGU character (non-general use character)].

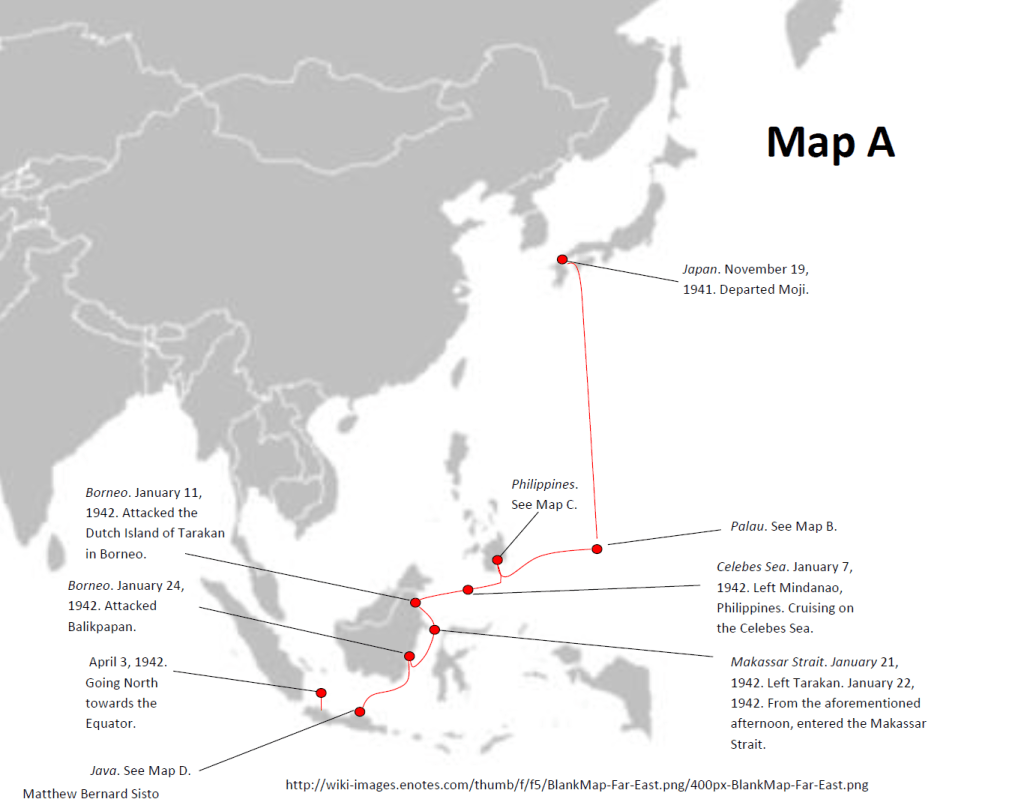

4.昭和一六(しょうわいちろく).一一(いちいち).一九(いちきゅう).門司(もじ)出(しゅっ)帆(はん)南(みなみ)太平洋(たいへいよう)巡航(じゅんこう)

Showa 16. 11. 19 (November 19, 1941). Departed Moji. Sailing [cruising] south in the Pacific Ocean [The second to last character may be a variant of 巡, as this makes sense when substituted].

5.一一(いちいち).二(に)八(はち).南洋(なんよう)パラオ(ぱらお)諸島(しょとう)コロル(ころる)着(ちゃく)

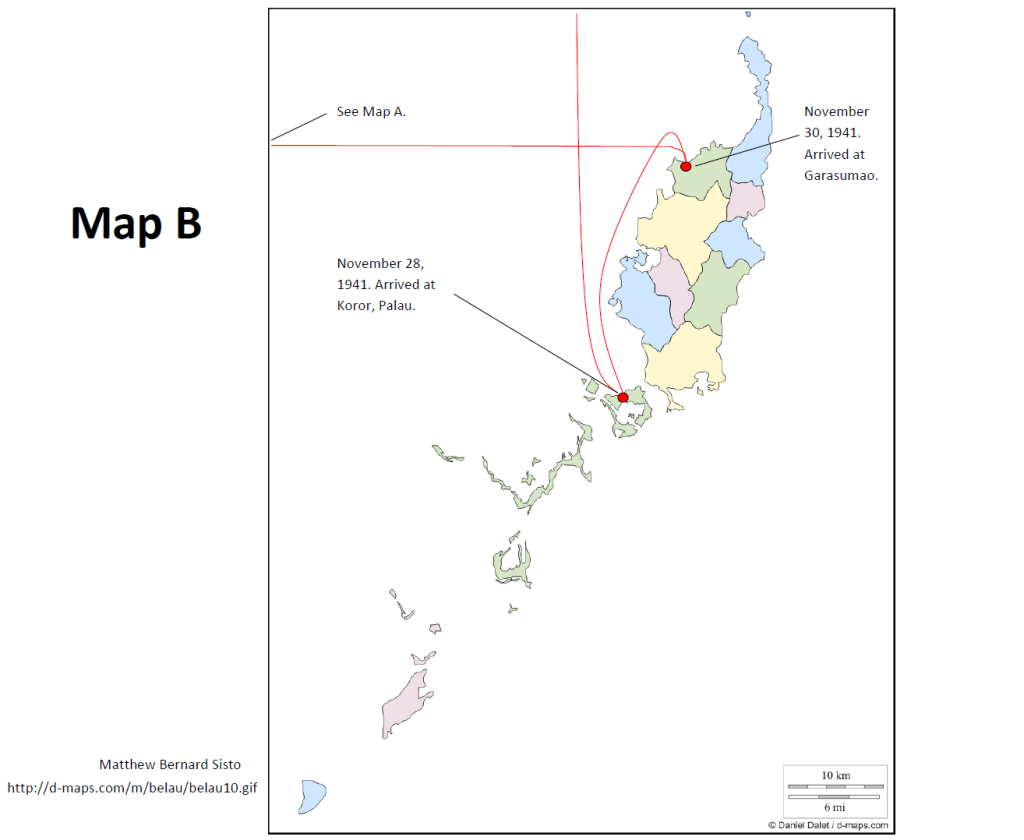

November 28, 1941. Arrived at Koror, Palau in the Southern Ocean [コロル or Koror was smudged/corrected, making the first character of the three difficult to read. After research, I have presumed the first character to be コ and the island name Koror. Southern Ocean may be a reference to the Pacific Ocean or the area of the Micronesian Islands, of which Palau is a part of].

6.一一(いちいち).三〇(さんぜろ).ガラスマオ(がらすまお)島(しま)着(ちゃく)

November 30, 1941. Arrived at Garasumao Island [in Palau].

7.一(いち)二(に).八(はち).午前(ごぜん)11(じゅういち)時(じ)50(ごじゅっ)分(ぷん)

8.宣戦(せんせん)市告(しこく)ス(す)

[Columns 7 and 8 combined] December 8, 1941. 11:50AM. The city has warned that war has been declared [The particle ス may be rarely used to indicate plural forms, just as an English speaker would add “s” to “car” to make the plural form “cars”. If this is the case, then it could be said that multiple warnings were made].

9.昭和(しょうわ)一(いち)七(しち).四方(しほう)拝(はい)船上(せんじょう)ニテ(にて).

Showa 17 (January, 1942). [Unsure of the true meaning of this sentence. After researching, I have theorized that it could be read, “Paid respects to the person in charge while on board. The particle ニテ is an indication of location where an event happened].

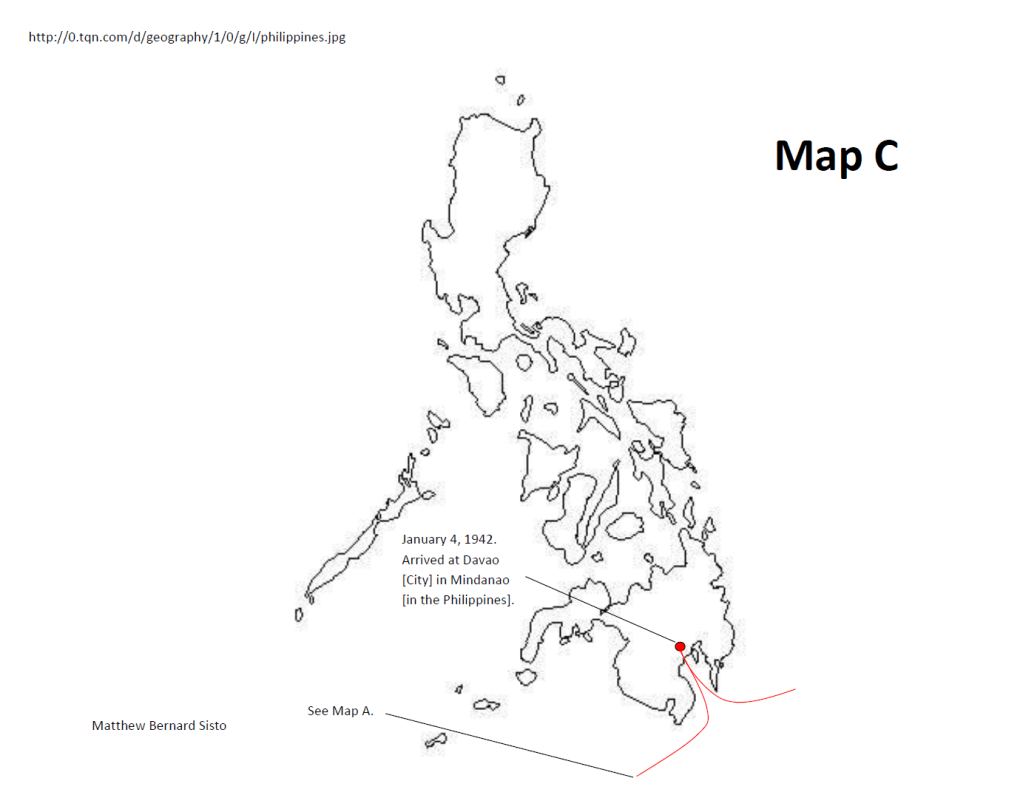

10.一(いち).四(し).ミンダナオ(みんだなお)島(しま)ダヴオ(だヴお)着(ちゃく)

January 4, 1942. Arrived at Davao [City] in Mindanao [in the Philippines].

11.一(いち).七(しち).右(ゆう)地(じ)出(しゅつ)発(ぱつ)セレベス(せれべす)巡航(じゅんこう)海(うみ)

January 7, 1942. Left Mindanao, Philippines. Cruising on the Celebes Sea.

12.一(いち).一一(いちいち).蘭預(らんよ)ボルネオ(ぼるねお)

[see number 13 for translation]

13.タラカン(たらかん)島(しま)攻撃(こうげき)

[Combined Columns 12 and 13] January 11, 1942. Attacked the Dutch Island of Tarakan in Borneo.

14.一(いち).二(に)一(いち).右(ゆう)地(じ)出(しゅつ)航(こう) 二(に)二(に).午(ご)右(ゆう)ヨリ(より)

15.マカッサル(まかっさる)海峡(かいきょう)ニ(に)入(はい)ル(る)

[Combined Columns 14 and 15] January 21, 1942. Left Tarakan. January 22, 1942. [It is possible that the next four characters say, “From yesterday at noon,” or, “from the aforementioned noontime,” as ヨリ could be 于 in kana form, which means “from” or “going.” 右, usually meaning “right”, can take on the meaning “aforementioned” in vertical writing]. From the aforementioned afternoon, entered the Makassar Strait.

16.一(いち).二(に)三(さん).午前(ごぜん)四(よ)時(じ)赤道(せきどう)南下(なんか)ス(す)

January 23, 1942. 4:00AM. Heading south of the Equator [The particle ス is once again present, though its role is unclear in this context. I have theorized, that ス could possibly be a further abbreviated form of スト, which is an abbreviated form of “strike.” If correct, this could be a reference to the impending attack mentioned in the next column].

17.一(いち).二(に)四(し).バリックパパン(ばりっくぱぱん)攻撃(こうげき) 二(に)五(ご)[unidentifiable kanji]地(じ)上陸(じょうりく)

January 24, 1942. Attacked Balikpapan. January 25, 1942. Disembarked on land [I am unsure of this latter sentence, as the kanji after 五 was unidentifiable to me. I inferred the meaning of the sentence as what is written above].

18.二(に).一一(いちいち).紀元節(きげんせつ)BPM[unidentifiable kanji]院(いん)ニテ(にて) 二(に).二(に)四(よん).同地(どうち)出(すい)港(こう)

February 11, 1942. Empire Day [I was unable to put the rest of this sentence together. The kanji before 院 was unrecognizable to me. In addition, I was unable to uncover the meaning of “BPM”].

19.三(さん).一(いち).ジヤヴァ(じやヴぁ)攻撃(こうげき)中部(ちゅうぶ)クラ(くら)ーガン(がん)東方(とうほう)上陸(じょうりく)

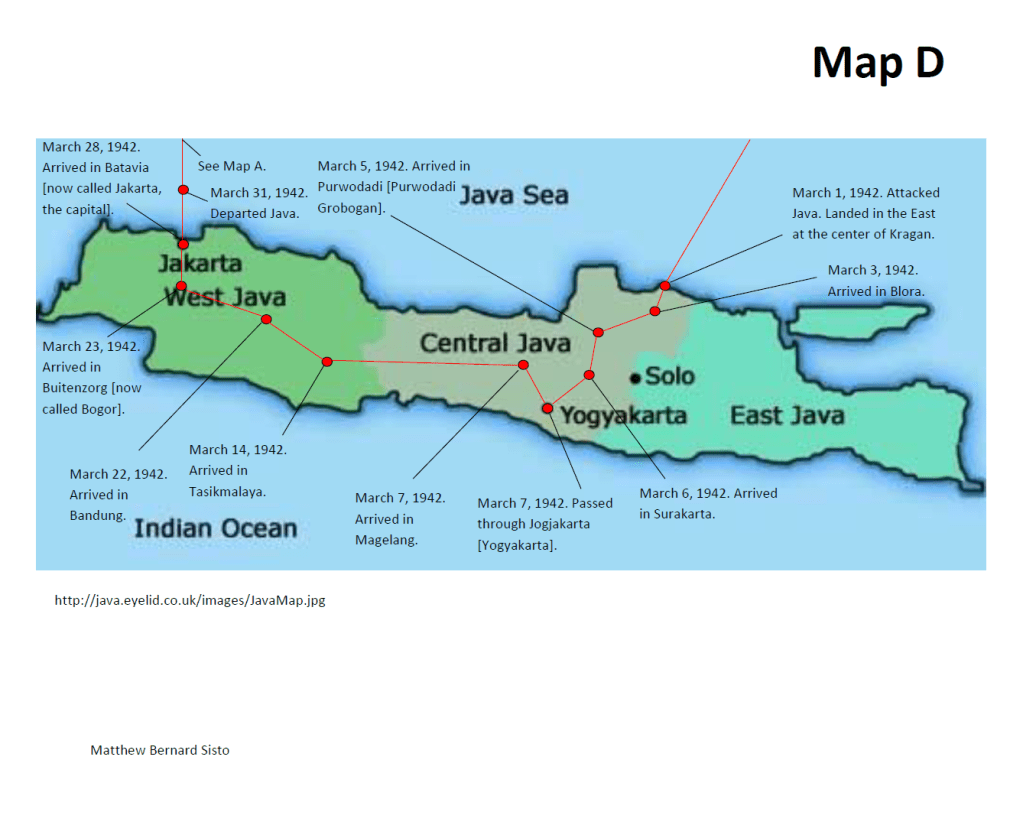

March 1, 1942. Attacked Java. Landed in the East at the center of Kragan.

20.三(さん).三(さん).ブロラ(ぶろら)ー着(ちゃく) 三(さん).五(ご).ヴルオ(ヴるお)ーダヂ(だぢ)着(ちゃく)

March 3, 1942. Arrived in Blora. March 5, 1942. Arrived in Purwodadi [Purwodadi Grobogan].

21.三(さん).六(ろく).(3.9)スラカルタ(すらかるた)着(ちゃく) 三(さん).七(しち).ジョキジヤカルタ(じょきじやかるた)通(つう)マゲラン(まげらん)着(ちゃく)

March 6 [Though the 3.9 is peculiar, making me wonder whether or not this was a correction in the date to March 9], 1942. Arrived in Surakarta. March 7, 1942. Passed though Jogjakarta [Yogyakarta] and arrived in Magelang.

22.三(さん).一(いち)四(よん).タシキマラヤ(たしきまらや)着(ちゃく)

March 14, 1942. Arrived in Tasikmalaya [actually written タシクマラヤ].

23.三(さん).二(に)二(に).バンドン(ばんどん)着(ちゃく) 三(さん).二(に)三(さん).ボイ(ぼい)テンゾルフ(てんぞるふ)着(ちゃく)

March 22, 1942. Arrived in Bandung. March 23, 1942. Arrived in Buitenzorg [now called Bogor].

24.三(さん).二(に)八(はち).バタヴィ(ばたヴぃ)ア(あ)着(ちゃく)

March 28, 1942. Arrived in Batavia [now called Jakarta, the capital].

25.三(さん).三(さん)一(いち).右(ゆう)地(じ)出(しゅつ)航(こう) 四(よん).三(さん).赤道(せきどう)北上(ほくじょう)

March 31, 1942. Left the aforementioned place [most likely referring to Java itself]. April 3, 1942. Going north towards the Equator.

I think one particular point of interest is columns 7 and 8. Why was war declared and against whom? Take note of the date: December 8, 1941, the day after Pearl Harbor.

Another chilling factor is where the journal ends. The last thing he says is that he is heading toward the Equator, but there are no entries after this. From what I understand, this flag was found on the soldier’s body. It is possible that he was killed in the Battle of Timor, a resistance against Japanese forces by the Allies which started in February. So, the timeline makes some sense, as he was fairly consistent with his updates until March 31st. Although he said he was headed toward the Equator, we can’t assume that’s where he ended up. The forces may have been rerouted to assist those which were fighting against the Allies.

Another possibility is that he stopped recording on the flag because he was simply running out of room. There is space for a few more columns, but perhaps he either stopped writing or found another medium to use. I vaguely recall that the flag may have been found on him at the Battle of Iwo Jima, but my memory on that is foggy. If that is true, it would lend more credence to this second theory.

If you are a history buff or are curious to know more, you can read about the Japanese Dutch East Indies campaign here. Many of the battles and places mentioned in the flag are located in the article or at the bottom (such as the Battle of Tarakan).

The Map

In addition to the translation, I created a map which outlines the soldier’s travels in the pacific. This was one of the coolest parts of the project as it really brought a cohesion to the journal entries. The maps guide you through one another, but Map A is the main map and the other three are used to zoom in to be able to see the detailed parts of his travels. Credit for the maps used as a foundation are given in each image.

But, where is the flag now…?

Great question. I have no idea.

From what I understand, it was supposed to be donated with our translation to the National Museum of the Marine Corps in Quantico, VA. After this though, I have not heard anything about it. I’ve tried searching for it online and through the website, but I am unable to locate it. My hope is that it is there and one day I’ll be able to go to the museum and see it. But until then, it will remain a mystery to me. Unfortunately, my Sensei never found out its true destination either.

Therefore, for me, it lives on in my photographs and the project documents I have created. This was one of the most difficult projects for me at the time because it truly stretched my language abilities, of which I had so little at the time. I had to very quickly learn how to search up kanji and unfamiliar terms which in my own native tongue were already difficult.

But, as I said before, this was not a project I wanted to pass up. As my most recent boss likes to say, “Say yes now, figure out how later.” And that’s exactly what I did. Did I find myself in deeper than I thought? Yes. Yet, I found a way to not only get up to speed quickly, but also to go above and beyond what I was asked.

It’s these kinds of projects – where you are scared and feel the gravity of your actions – that you need to take. They push you to your limits and allow you to find new levels of competency you didn’t think were possible. And they allow you to be part of opportunities which you look back on as priceless.

Categories